When President Trump talks about the “hundreds of billions of dollars of fraud” that Elon Musk’s cost-cutting team has uncovered in the federal government, he sometimes singles out one program with particular scorn.

“Twenty million dollars for the Arab ‘Sesame Street’ in the Middle East,” the president told a joint session of Congress this month, as he laid out the case for a smaller, more efficient government free of what Republicans call “woke” ideology.

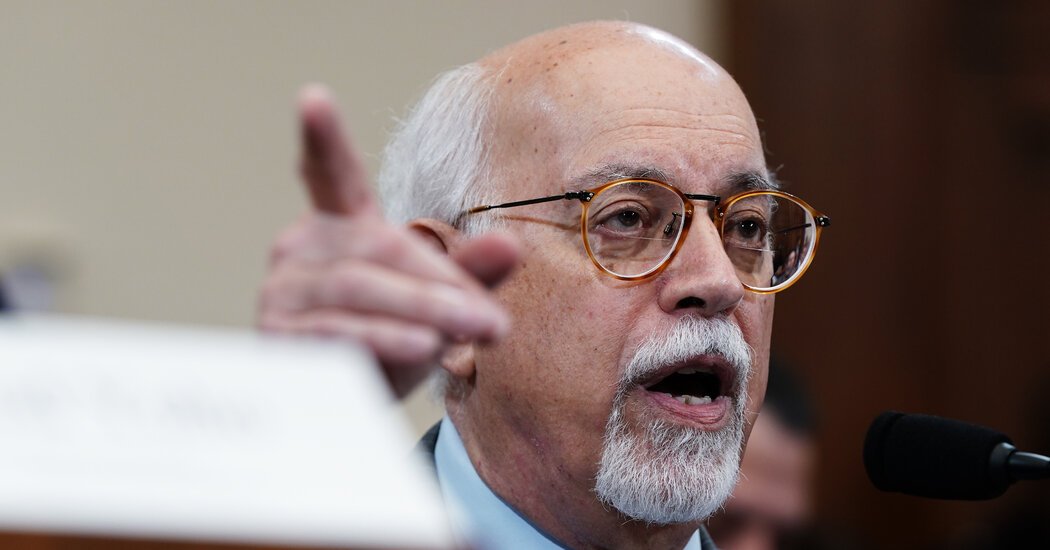

But the Arabic-language version of “Sesame Street” was not just the purview of progressives. It has been supported, in its various iterations over the years, by members of both parties, including Andrew S. Natsios, a conservative Republican who led the U.S. Agency for International Development under President George W. Bush.

“The biggest weapon against Al Qaeda and Islamic extremism is ‘Sesame Street,’” Mr. Natsios said in an interview, recounting how successful the show had been in Egypt when the American government helped fund it during his term in office. Children would watch the show in the morning before breakfast, he said, helping them adopt more positive attitudes toward the West.

The show is a textbook case of what is known as soft power, the kind of noncoercive, long-term diplomacy designed to build good will and influence around the world, a strategy Mr. Trump has largely cast aside in favor of more transactional, strong-arm tactics.

As Mr. Trump and Mr. Musk slash their way through the federal work force, their claims of fraud are often differences of opinion about policy — not examples of criminal wrongdoing or corruption.

They have falsely accused media companies, for example, of taking payoffs from Democratic administrations, when the payments in question were subscriptions purchased by both Republican and Democratic administrations.

They have exaggerated long-known issues with Social Security data, falsely claiming that tens of millions of dead people might be receiving benefits.

And they have described programs aimed at helping lift the world’s poor out of poverty — such as one that bolstered female entrepreneurs or another that helped countries create tourism industries — as corrupt junkets.

“A lot of the things they’re criticizing are ridiculous,” Mr. Natsios said. “What we would do is we find small businesses. Let’s say they’re making dresses in Ukraine that are of high quality enough that they could sell in the European market, and we take the women to a trade show in the U.S. or in Paris to help grow their business. This is one of the things that was listed as some kind of a junket.”

Many Americans support efforts to shrink the size of government and cut spending, and disagree with the idea that the United States should provide aid to fight disease and poverty overseas. Mr. Musk says his Department of Government Efficiency has eliminated wasteful spending on things like unneeded software, unused Zoom licenses and underused leases.

But the Trump administration also insists it is uncovering something more sinister — widespread fraud and “kickbacks” — as it tries to justify across-the-board cuts. In his address to Congress, Mr. Trump encouraged Attorney General Pam Bondi to look for such cases.

“We’re searching right now,” Mr. Trump said. “In fact, Pam, good luck. Good luck.”

Asked whether the Trump administration had found specific cases of fraud, Karoline Leavitt, the White House press secretary, argued that perceived waste essentially amounted to fraud.

“I think all Americans would agree that funding mastectomies in Mozambique is not something that the American people should be funding,” she said. “I think it’s fraudulent that the American government has been ripping off taxpayers in this way.”

Ms. Leavitt appeared to be referring to U.S.A.I.D.’s decades-long work with Mozambique’s government to make health care accessible to the country’s rural poor.

On social media, DOGE did accuse one company of potential wrongdoing. Ed Martin, the interim U.S. attorney for the District of Columbia, said that he was investigating a firm that was paid to house unaccompanied migrant children at an empty Texas facility.

The firm, Endeavors, denied the allegations.

“First and foremost, let me be clear: Any claims of corruption or mismanagement are completely baseless,” Chip Fulghum, the firm’s chief executive, said in a statement.

Dylan Hedtler-Gaudette, the director of government affairs at the Project on Government Oversight, a nonprofit watchdog that examines Pentagon contracts, said the Trump administration has not uncovered significant new cases of fraud.

“They’re just going after programs that are politically advantageous to them in some way,” Mr. Hedtler-Gaudette said. He added: “The problem with waste is, that’s very much an eye of the beholder. One person’s waste is another person’s critical investment.”

Asked for evidence to support its claims of uncovering fraud and abuse, the Trump administration provided several lists to The New York Times:

-

One contained projects that could be described as wasteful spending depending on one’s political views, but not fraud. The list included foreign aid programs that the Trump administration does not believe should receive American dollars; others that promoted environmental causes; and contracts related to diversity and inclusion goals.

-

Another was a compilation of studies from the Government Accountability Office, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services and other federal sources that track improper payments and wasteful government practices. One G.A.O. study, for instance, estimated that the federal government loses $233 billion to $521 billion annually to fraud. The studies were not conducted by Mr. Musk, his cost-cutting team or the Trump administration. They were findings from the Biden administration.

-

A third was a database of canceled contracts and other cuts that Mr. Musk and his DOGE team claim have saved the federal government roughly $115 billion. A New York Times review of Mr. Musk’s data revealed accounting errors, incorrect assumptions, outdated data and other mistakes. While the DOGE team has made billions of dollars in cuts, its database does not include the specific allegations of criminal fraud or “kickbacks” that Mr. Trump has described.

Whenever large amounts of money change hands, there is a significant risk of fraud. In 2023, for instance, the Justice Department said it had charged more than 3,000 defendants for offenses related to pandemic fraud and seized more than $1.4 billion in relief funds. Those investigations were aided by inspectors general trained in finding abuse.

But while the Trump administration says it is cracking down on fraud, it has fired nearly 20 inspectors general whose mission was to uncover fraud, waste and abuse.

One of them, Michael J. Missal, who spent nine years as inspector general for the Department of Veterans Affairs, said that his team had saved the government over $45 billion. He noted that they uncovered evidence that led to the conviction of a serial murderer.

“They don’t want independent people running these offices, because we typically have hard-hitting reports that may not make the administration look favorable,” he said. “If they found fraud, there should be criminal cases. I haven’t seen any criminal case.”

Mr. Missal is suing to get his job back.

As for the Arabic-language “Sesame Street,” the Trump administration’s cuts mean that an educational companion program to the show and a translation into a local dialect will be discontinued in Iraq. The eliminated funding had provided books, classroom materials and training for teachers in Iraq to use in early childhood development centers, according to the Sesame Workshop, the nonprofit that makes the educational program.

But the main version of the show, called “Ahlan Simsim,” will continue to air in the Middle East and North Africa. The MacArthur Foundation, a charitable foundation, in partnership with The International Rescue Committee, an aid group, have funded the program since 2018.